-

VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN IN PAPUA NEW GUINEA

-

DANGER ON THE STREETS

Papua New Guinea is a dangerous place for women or ‘meri’ as they are called in Tok Pisin, the local language. Violence against women is seen as normal. According to recent statistics from the Papua New Guinea National Department of Health, more than two thirds of women have experienced physical or sexual violence, one third were subjected to rape and 17% of sexual abuse involved girls between the ages 13 and 14. One of the world’s leading humanitarian charities, Doctors Without Borders, claim that they are dealing with levels of gender violence normally only experienced in war zones.

www.gulickhhc.com/drugs/erectile-dysfunction/ inhousepharmacy.vu reviews fildena 100mg fildena 100 reviewsThe main danger comes from the Raskol gangs that rule the settlements in big towns and the capital city. Every day most of the crimes committed are against women from the Port Moresby slum areas. Peter Moses, one of the leaders of “Dirty Dons 585” Raskol gang, states that raping women is a “must” for the young members of the gang. In some New Guinean tribes when a boy wants to become a man, he should go to enemy’s village and kill a pig. After that his community will accept him as an adult. In industrial Port Moresby women have replaced pigs. “First, a young gang member should steal something, money or a car — and he will be admitted to the gang. After that he must prove that his intentions are serious and he must rape a woman to complete his initiation. And it is better if a boy kills her afterwards, there will be less problems with the police”, says Moses, 32, who claims to have raped more than 30 women himself.

-

02. Port Moresby, the capital of Papua New Guinea, is considered to be one of the most dangerous cities in the world.

-

03. A woman walks down the street in Lae, PNG's second largest city. Lae has the second highest crime rate in PNG, exceeded only by Mount Hagen, PNG's third largest city.

-

04. A group of girls cross the street in Mount Hagen, the third largest town of Papua New Guinea with the highest rate of violence in the country.

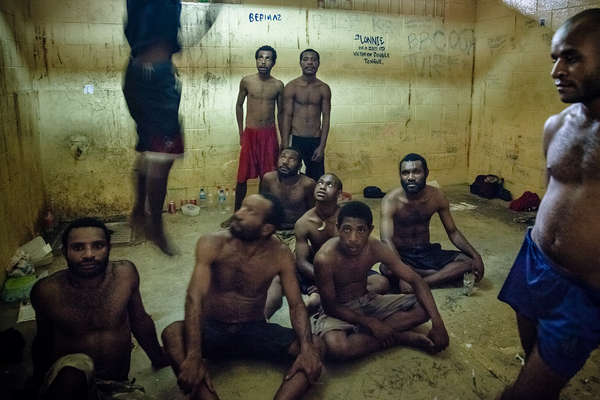

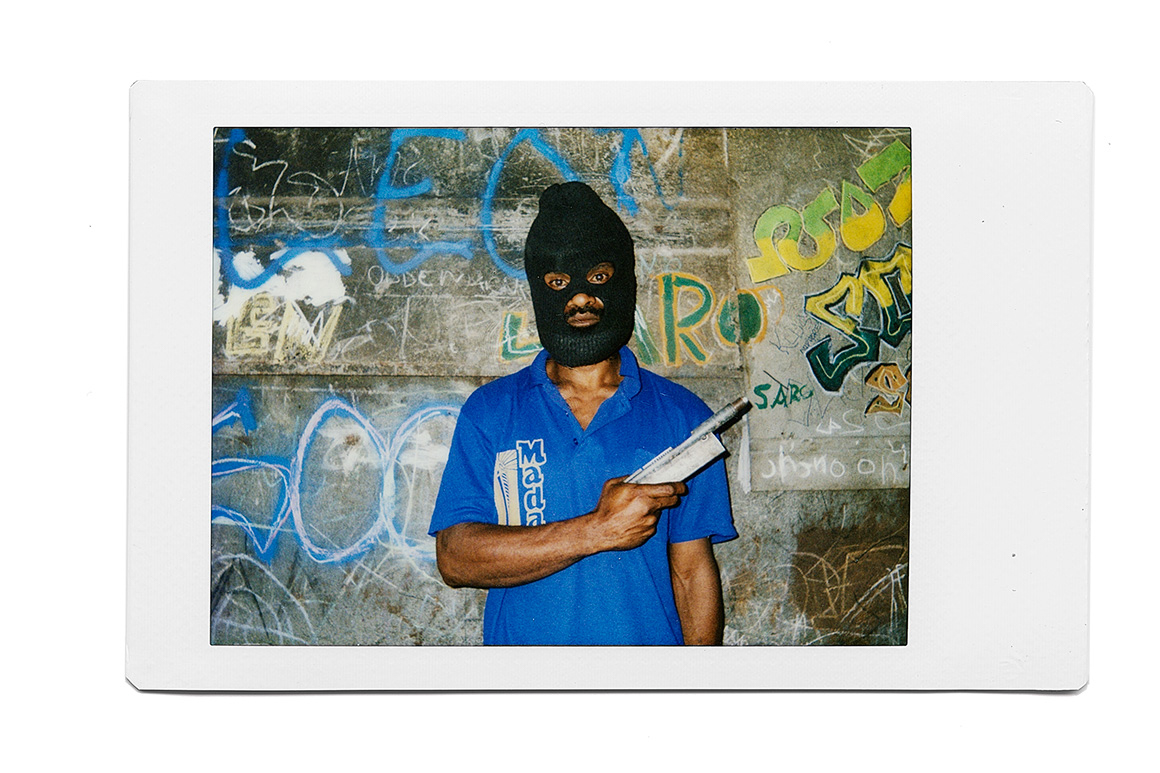

05. Members of the Raskol gang ‘Dirty Dons 585’, in the 9 Mile Settlement, Port Moresby. The gang committed a set of rapes and armed robberies. ‘Dirty Dons’ admit that two thirds of their victims are women.

-

06. Goro, 31, one of the members of “Lauma,” a raskol gang, hides his gun in a hollow tree trunk. “The police search for the guns in our houses, but we never keep our weapons at home”

-

07. Weapons confiscated from Raskol gang members during attacks on women, Top Town Police Station, Sexual Offences Squad, Lae town, Morobe Province

-

08. Members of “Lauma” raskol gang show their weapons in their safe house in one of the settlements of Port Moresby.

-

09. A doctor of the Antenatal Clinic in Port Moresby examines a 14-year-old girl, who was raped by a 40-year-old lawyer. The victim said that the man was a friend of her family so she didn’t suspect anything when he offered her a lift to the market. However, he instead drove the girl to his house, raped her and then left her on the road of the settlement. The girl’s father brought his daughter to the hospital but wasn’t sure if he wanted to sue the rapist.

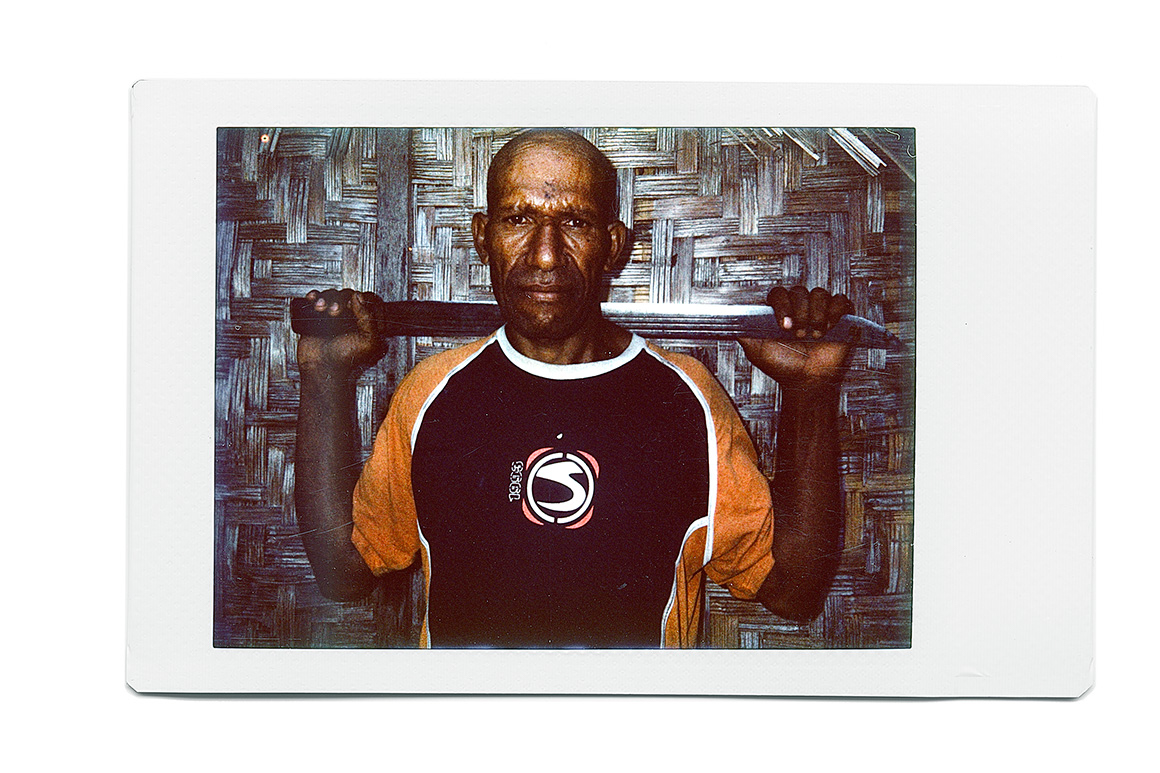

10. Mafu, 30, with a home made gun in one of the settlements of Port Moresby.

-

11. A boy poses with the wooden gun near his family house in ATS settlement, Port Moresby. For many boys raskols are heroes and some kids join the local gangs at very young age.

-

12. Eight-year-old Hilda (name changed), a child victim of sexual abuse in her family’s house in Kundiawa, Chimbu Province. She was raped by a stranger on the street near her school. Many people watched it, but no one helped her or called the police.

-

13. Hilda, 8, a victim of sexual abuse, plays in her room.

-

14. Men on the street of Mount Hagen, third largest town of Papua New Guinea with the highest rate of violence in the country.

-

15. Women wait in a queue to speak to police officers of the Sexual Offences Squad in Top Town police station, in Lae. The Sexual Offences Squad receives reports from 10 to 20 women a day.

-

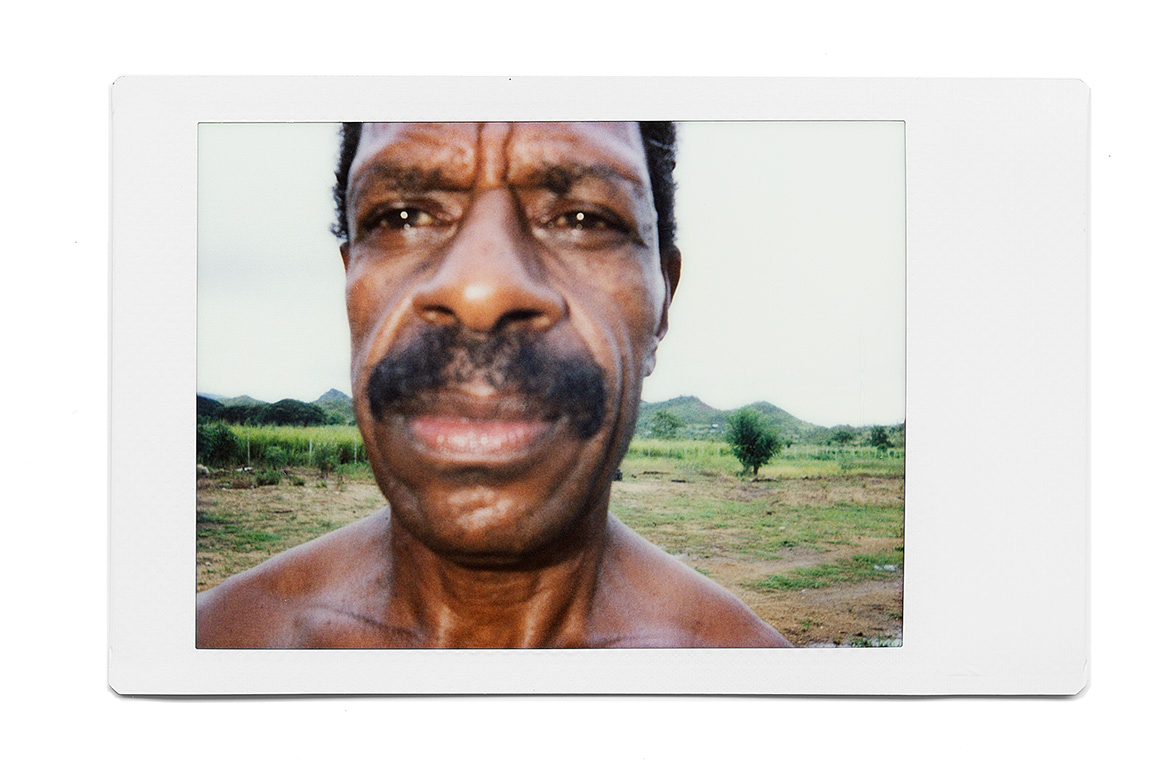

16. Peter Moses, 32, one of the leaders of the “Dirty Dons 585” raskol gang. He says that raping women is a “must” for the young members of the gang. Peter himself claims to have raped more than 30 women.

-

17. A taxicab waits for clients near the Harbor City shopping center, Port Moresby. Taxis in Port Moresby are the most dangerous public transport for women – many cases of rape and attacks on female passengers occur in cabs by drivers and their friends.

-

18. Alex, 34, a taxi driver. Alex never drives his car without his big knife.

19. Helen, 40, mother of seven children was attacked by a “cannibal” in the central part of Port Moresby. The attacker bit off Helen’s lower lip and tried to sink his teeth into her throat. Police arrested the man and found out that this was his third attempt to eat human flesh. After spending three days in the hospital, Helen went to the police station to initiate criminal proceedings against the cannibal, but discovered that he had been released due to lack of a complaint. 19. Helen, 40, mother of seven children was attacked by a “cannibal” in the central part of Port Moresby. The attacker bit off Helen’s lower lip and tried to sink his teeth into her throat. Police arrested the man and found out that this was his third attempt to eat human flesh. After spending three days in the hospital, Helen went to the police station to initiate criminal proceedings against the cannibal, but discovered that he had been released due to lack of a complaint.

-

20. A nurse takes stitches out of Helen’s face after her lip reconstruction surgery by Interplast doctors. Port Moresby General Hospital. International charities ChildFund Australia and Interplast Australia & New Zealand worked together to help Helen access the health system and receive surgery to reconstruct her lip. See Helen's recovery story on https://vimeo.com/83991442

21. A member of “Lauma” raskol gang in a settlement of Port Moresby.

-

22. Omsy (right), an ex-member of the Kips Kaboni gang, with his wife Carol in their house. Omsy was a rapist and thief but left the gang a few years ago to become a bass guitarist. Omsy says that when he quit the gang he also stopped beating his wife. However he keeps his handmade gun to protect his family, as they live in Kaugeri, a dangerous settlement in Port Moresby.

-

24. Early in April 2012, six-year-old Julie (name changed) was kidnapped and assaulted by four men in Lae. The men raped the young girl for eight hours and then left her in the street. Julie spent more than three weeks in the hospital. Because of the injuries inflicted on her, Julie can barely walk and can never have children. Her tormentors were arrested by the police.

-

25. A police officer of the mobile squad on patrol in the city. The squad acknowledges that about 70% of crimes in Port Moresby involve violence against women.

-

26. A policeman beats a man on the street in the town of Minj, Jiwaka Province. The man was suspected in a sexual assault attempt and police arrested him, using force to take him to the police station for interrogation.

-

27. A policeman interrogates a suspect in a sexual assault case in the Boroko police station, Port Moresby.

-

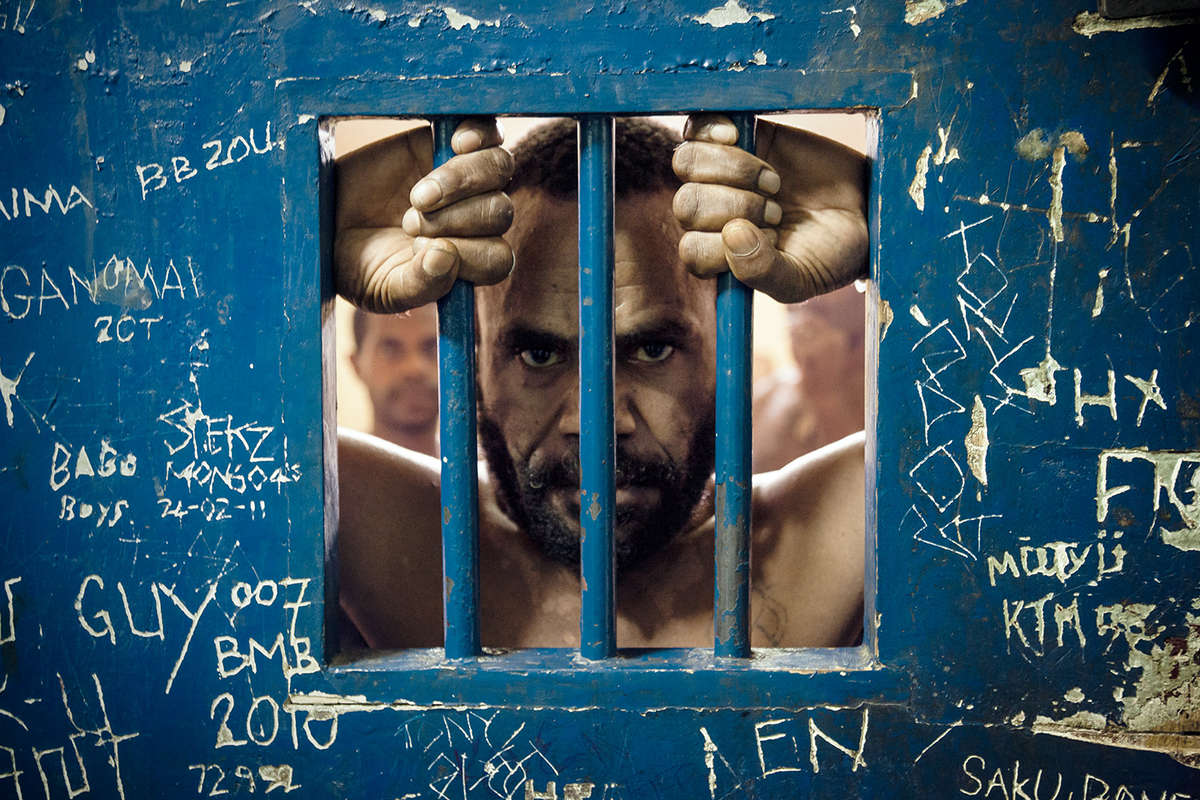

28. A prison cell in the Boroko police station is mostly filled with murderers and rapists. The police officers on duty admit that it is very rare that men are imprisoned for accusations of domestic violence.

-

29. Andres, 39, accused of multiple rapes, waits for his court date in a cell in the Boroko Police Station.

-

DANGER IN THE HOME

In Papua New Guinea a large percentage of local men don’t respect ‘meri,’ constantly beating them, often using bush knives and axes. Men believe that after they have paid a bride price — following local tradition when a bride’s parents receive payments from the groom’s family — they fully possess a woman and can treat her the way they treat a purchased vehicle.

Many cases of domestic violence occur because of alcoholism and jealousy, as men in Papua New Guinea often have two or three wives at the same time. Rejected and beaten women are often kicked out of their homes and onto the street, where they then become easy targets for Raskol gangs. Violence against women is rarely brought to court. Most assailants are kept in a cell at the police station for a couple of days and then released. The police claim the low rate of convictions stems from the fact that victims often fear filing a statement or that many wives take pity on their husbands and insist on the termination of the case.

Tessie Soi, a social worker and the director of the Family Support Center in Port Moresby’s General Hospital, says that most women would rather tolerate beating and coerced sex than be left without the support of a man. “The problem is that men start feeling unpunished and continue treating their wives with a greater cruelty, even when pregnant. This often results in a loss of the child or death of a woman. That’s why I insist that once violence has been reported to the police, there is no way back”.

Perpetrators also escape justice because of money. To file an assault report with the police, an abused women must first obtain a medical statement, which costs. Also, a woman has to buy fuel for the police car, as nowadays police stations do not receive enough financial support. Fuel costs are high and, in rural areas, women cannot afford the expense. Furthermore there is no guarantee that police will not take a bribe from a landed perpetrator to release him later.

-

31. Marcela from Hanuabada village during a bride price ceremony. Bride Price is an ancient Papuan tradition where the husband pays the bride’s parents for her. Men often then believe that, after they have paid a bride price, they fully possess a woman.

-

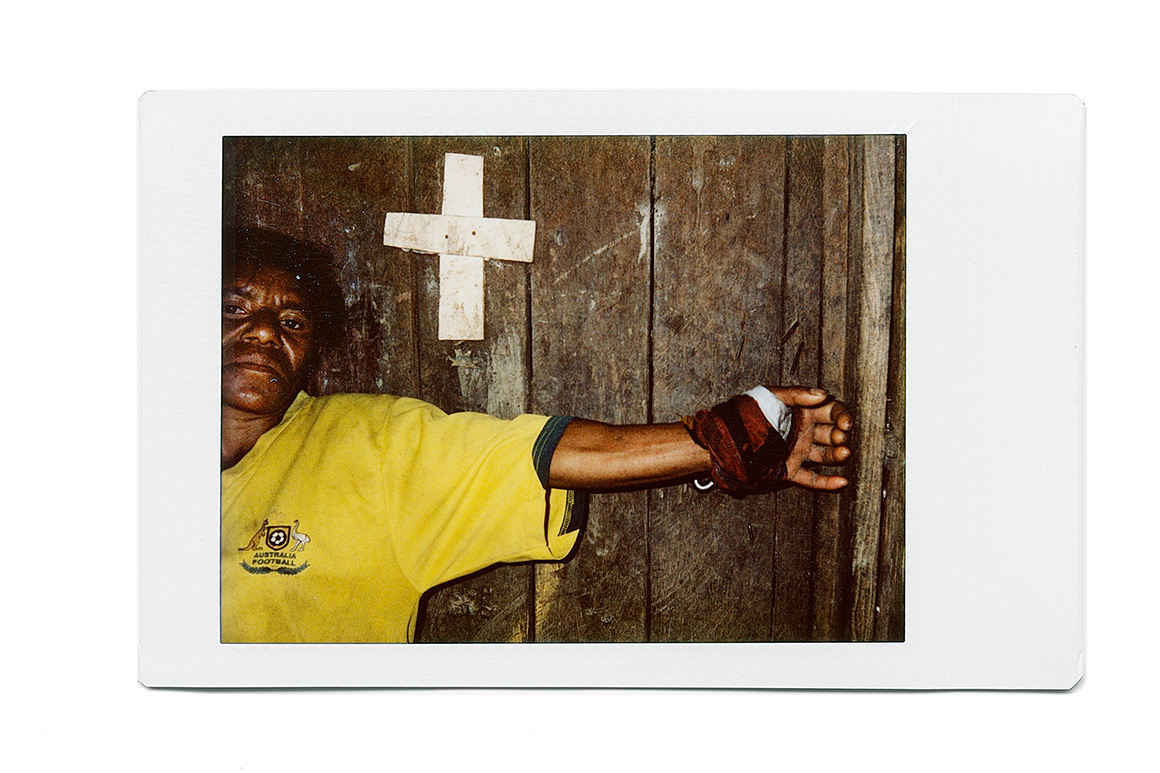

32. Richard Bal shows off the disfigured ear of his wife, Agita, in their house in Port Moresby. In December 2010, after coming home drunk, Richard took a bush-knife and cut off half of Agita’s left ear. He spent one night in the police station and was released the next morning due to "insufficient evidence" to initiate criminal proceedings. Agita’s relatives did not allow her to leave Richard, having received 500 kina compensation from him for the "potential damage" caused.

35. A security guard sits on a billiard table in one of the night clubs of Port Moresby. Most of the cases of violence against women happen on a weekend, when much of the male population of Papua New Guinea gets very drunk after the work week.

-

36. Daniela Solange, 34, with her one-year-old son, Joseph Raphael, in their house. Many women and children in the settlements live in makeshift houses constructed from found material. They live without locks or security of any kind to protect them from attacks.

-

37. A man dances with a young woman on Friday night in 'Greenland' bar, Kundiawa town, Simbu Province.

-

38. Victims of domestic violence Diane, 22, (left) and Welda, 22, (right), in the refuge house of the Nana Kundi crisis center in Maprik, East Sepik Province.

-

39. Rose’s violent husband had often attacked her with a knife and she feared he would kill her. But the threat he posed became even more ominous when he hurt their baby girl. Rose suspected her baby had been sexually assaulted and took her to hospital, where medical staff confirmed her worst fears. She left her husband and sought shelter in Haus Ruth, one of the few refuges in Port Moresby.

-

40. Jacklyn’s disabled daughter in the Haus Ruth refuge. Jacklyn and her children were abused by her stepfather.

-

41. Child’s drawing on the wall of the family support center in Kundiawa, Chimbu Province.

-

42. Nineteen-year-old Julie, with her son, shows off her prosthetic leg in front of her house in Kundiawa, Chimbu Province. At the age of nine months, Julie's father attacked her and chopped off her leg. When she went to the city of Lae in 2011 to be fitted for a new prosthetic leg she was raped by members of a local gang and later found out she was pregnant. She now lives with her son James (left) in Kundiawa town.

43. Helen lost her leg during a fight with her drunk husband, Alai. Alai chopped off Helen’s right leg with a bush knife in front of their young children who called for help. Alai was arrested by police, however after receiving treatment Helen left her home out of fear that her husband might be released. She returned when she found out Alai had died in prison.

-

44. A woman from Kundiawa holds her mobile phone with a screen picture of Jesus on it. Many Papua New Guinean women do not trust government institutions and seek aid and shelter from religious organizations and churches.

-

45. Rose, 21, a sex worker from “ten kina street” (five dollar street), Lae, Morobe Province. Rose left her house in Mendi after a year of living with a boyfriend who constantly beat her. Having found no support from her family and no protection from the police, Rose went to Lae in search of a better life. After weeks of unsuccessful searches for housing and employment, she became a “two kina meri” (one dollar women). Rose earns from 30 to 100 kina a day (15 to 50 dollars) and saves the money for purchasing her own house in one of the Lae’s settlements.

-

46. A heavily pregnant woman waits to be checked by a midwife at the Sehulea medical center on Normanby Island, Milne Bay Province. Many women die in childbirth because of lack of access to basic health services, with many medical outposts and clinics in remote communities closed due to lack of staff, equipment or medications. Also because of women’s low status in Papua New Guinea, many are not supported by their husbands when their babies come and they require urgent care.

-

47. Molly, 42, waits for her medical examination at the Family Support Center at Port Moresby General Hospital. Molly was brutally beaten by her husband, a security guard, who does not allow her to leave their house.

-

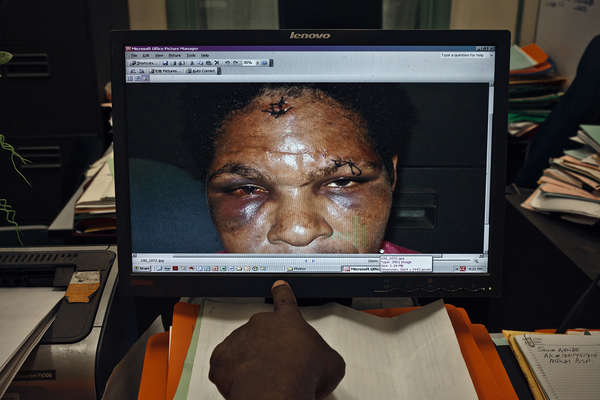

50. A police officer shows a photo of a domestic violence victim on his computer.

-

51. Vero, 37, lies unconscious in the emergency section of Kundiawa Hospital, Chimbu Province, after being brutally beaten by her husband for driving the family car without his permission.

-

DANGER IN SUPERSTITION

Sorcery-related violence is widespread in Melanesia. In Papua New Guinea it can take a savage form. In the Highlands Region witch-hunts occur in almost every province. Locals believe in ‘sanguma,’ witches, or ‘puri-puri,’ black magic. In case of an unexpected death in a village, residents often accuse a woman of sorcery, usually a relative of the dead person, and torture her, forcing her to confess that she is a witch.

The torture can involve cutting with machetes and axes. It may include burning with hot metal implements. Many of these ‘punishments’ are public and result in the victim’s death. Sometimes women are burnt alive. Even if the woman survives, she is expelled from the community permanently and cannot return home. Despite the widespread violence, the authorities of Papua New Guinea do not have a program to help victims of sorcery-related violence or to provide any shelter for these women. Cases of sorcery-related violence are rarely brought to court and sometimes even the police are involved in witch-hunts, supporting the perpetrators not the victims.

-

53. Dini near the grave of her son Bobby. After Bobby’s death Dini was accused of killing him using witchcraft and was brutally tortured by people from her village.

-

54. Dini's home village of Wormai in Сhimbu Province. Here in the past few years 8 women were accused of sorcery and attacked. Only few of them have survived.

-

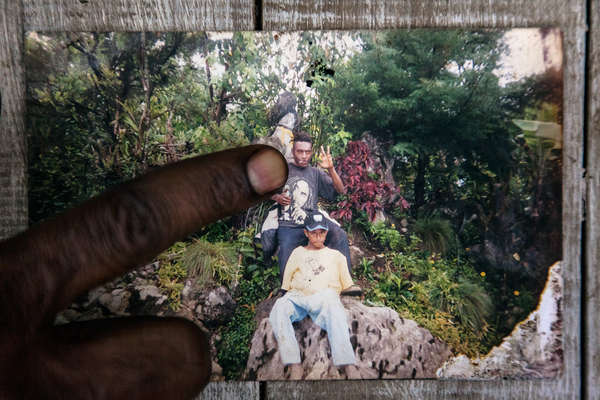

55. A photograph of Dini’s son Bobby (standing), who died from a stomach infection in 2011.

-

56. After Bobby’s funeral, five of his friends came to Dini’s house, accusing her of killing her son with "sanguma". They took her out and dragged her through the village to a pigsty, where they cut her body with bush knives and burning with hot iron bars. Dini survived and spent over ten months in the Kundiawa hospital. Her daughter paid for her treatment and never received any help from the local authorities.

-

57. Dini shows a scar on her right leg made by her tormentors with a red-hot iron

-

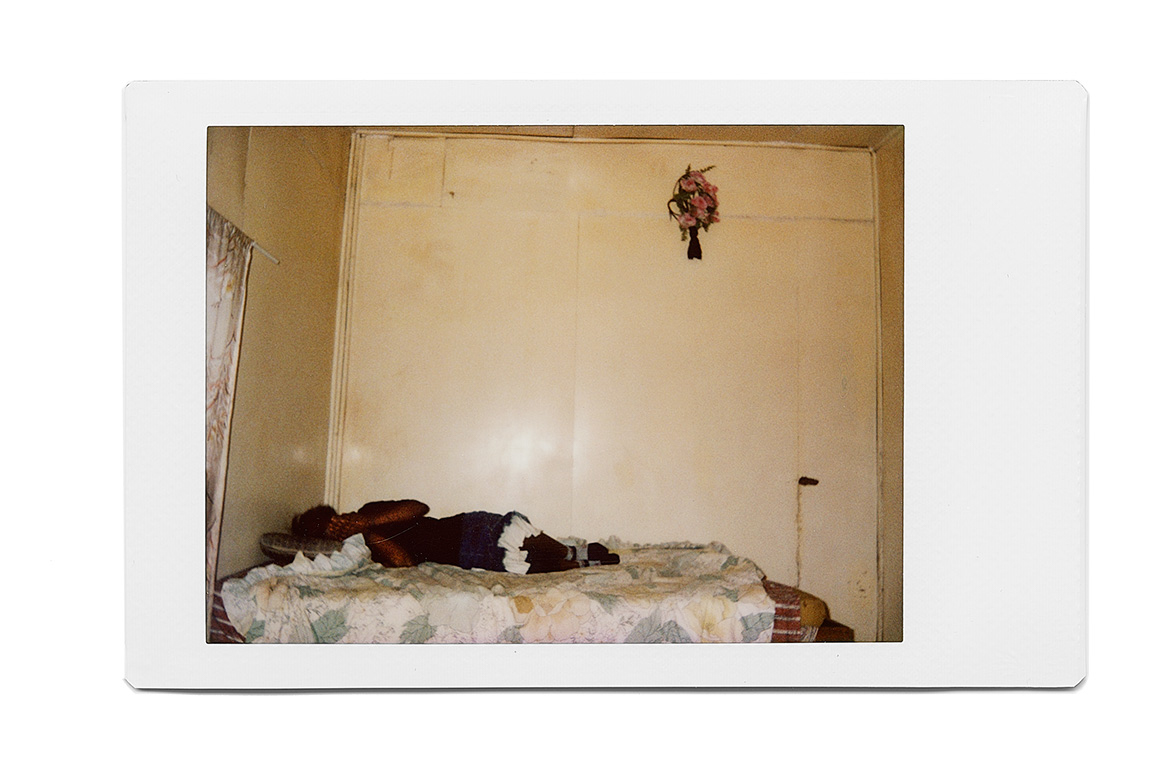

58. Dini lies on the bed in her house in Chimbu Province.

59. After spending nearly a year in the hospital, Dini came back to her village. Having been expelled from her community, it was a risk returning home but she had nowhere else to go. On her return, she lived in fear that she would receive further punishment. She barely left her house during daylight hours for several months. She was accepted back by the villagers but never received an apology from her attackers. They were never arrested.

-

60. Walne was accused of using sorcery to kill a young boy and hunted by her husband’s family. Narrowly escaping public execution, she is currently in hiding.

-

61. Jokar “Skull”, 28 years old, one of the gravediggers and night guards at a cemetery of Mount Hagen. “Skull” and his friends spend the night in the cemetery to guard the graves from “witches” who they believe come at night to steal bodies to use them for witchcraft. Armed with machetes and homemade guns, grave guards attack any moving target after dark, including animals, believing that witches use them to get close to the graves.

-

62. Emate lying in a hospital ward after surviving a sorcery attack. Her own sons accused her of using black magic that caused the death of her husband. Emate was burned with red-hot iron bars and beaten with hatchets, hammers and knives in front of all the villagers.

-

63. Wendi from Wara Chimbu village shows her scars. She was accused of sorcery by villagers who tortured her for three days.

-

64. People in a minibus in Mount Hagen, the Western Highlands provincial capital, which is considered to be the most dangerous place not only in Papua New Guinea but also in the whole Pacific Region. In early 2013, a 20-year-old woman, Kepari Leniata, was killed there after being accused of witchcraft. She was set on fire and burned alive in the center of the town in front of a crowd.

-

65. Rasta was accused of sorcery by her neighbors after the death of a local young man. She was set upon by a crowd at his funeral and beaten and strangled before she escaped. She lost her hand in the attack.

66. The mutilated hands of Rasta, who was tortured by people from her village.

-

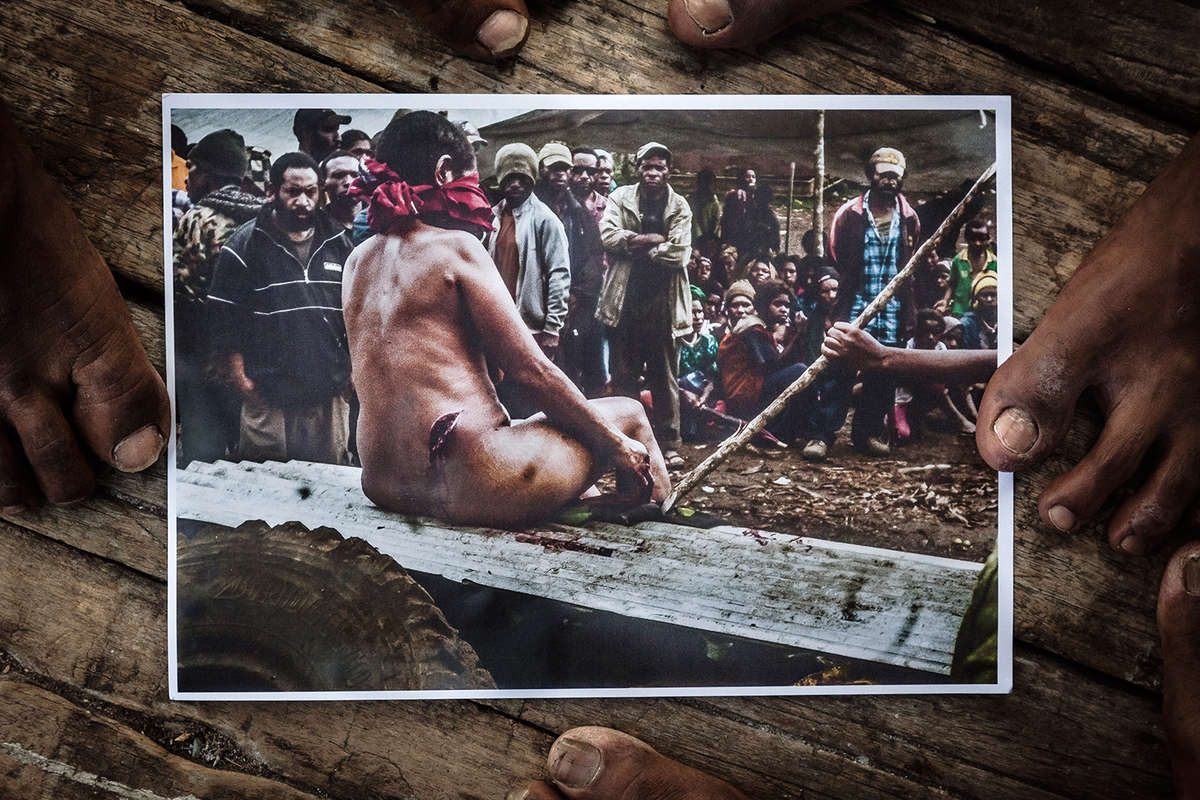

67. A woman advocate shows a photo of the torture of another woman, who was accused of being a sorcerer by people from her village. The torture happened at the beginning of August, 2012, in Southern Highlands Province. The crowd undressed the victim, tied her to a tree, beat her and burned her body with hot iron bars, planning to burn her alive. The violence was interrupted by a group of Catholics and the woman survived. Pictures of the torture were taken by a man from the crowd with a snapshot camera and, at a later date, given to the local Catholic parish and to the photographer. Fearing more violence, the woman in the picture is hiding from her tormentors in another province.

-

68. A photo of the torture of a woman who was accused of sorcery by people from her village. No one was charged with the crime.

-

69. Mary from Chimbu Province was accused of sorcery and attacked by villagers. She and her son barely escaped alive.

-

70. Jaskies Martin near the body of his mother Stolostika in Maprik district hospital, East Sepik Province. Stolostika was accused of sorcery by residents of her village and was beaten to death.

71. A woman looks down the valley from Kassam Pass, Morobe Province. The beautiful landscape of Papua New Guinea’s highlands belies the brutal reality of life in the region, where more than 90 percent of women report suffering gender-based violence.

-

AFTERWORD

The situation in Papua New Guinea is slowly changing. Women are raising their voice and can’t be ignored anymore by the local authorities.

In 2013 the PNG Parliament repealed the country’s controversial Sorcery Act that provided protection for the perpetrators accused of sorcery-related violence if they were acting to stop ‘witchcraft’.

The country’s Prime Minister, Peter O’Neill, publicly apologized to all the women of PNG for the high rates of domestic and sexual violence in the country. On September 18, 2013, Papua New Guinea passed the Family Protection Bill that, for the first time in PNG history, criminalizes domestic violence.

At the same time the PNG government reinstated the death penalty, which will apply to a long list of crimes including sorcery-related murder and rape. International organizations like Amnesty International and local human rights defenders believe that it is a step backward.

“Our work could become even more dangerous after the death penalty was brought back,” says Monica Paulus, who has worked with victims of sorcery-related- violence for several years in the Highlands Region of PNG. “Now the perpetrators will fear that they might be sentenced to death and will do everything to eliminate all the witnesses to their crimes, including those people who help the survivors.”

It is still too early to say whether the new laws will actually protect women or not. In a country where tribal rules and customs still hold sway in many remote communities, it will likely take years to stop injustice. But now, people are aware because local papers and social media are filled almost every day with horrific news about violence against women and girls. Still, Papua New Guinea remains one of the most dangerous places on Earth to be a woman.

-

CRYING MERI DIARIES

“Crying Meri Diaries” are my visual diaries that I wrote during several trips to Papua New Guinea, while working on the “Crying Meri” project.

With words and Polaroid images I kept a record of my thoughts and impressions, writing down dialogues with victims and perpetrators, and otherwise capturing the moments and events that surrounded me every day.

-

73. Port Moresby – a city where half of the female population is exposed to domestic and street violence. Rape, theft, armed robbery and carjacking are problems in and around the city.

In its brothels, teenage girls sell their bodies, having been sent there by their fathers and brothers. Raskol gangs operate in the settlements, raping and killing, but many of their crimes are never reported to the police. Even during the day, drunken men can be seen here beating their ‘meri’: wives, daughters and even mothers. And at night... At night it is better not to leave your fortress with its high wire fence. The city may misinterpret and fail to forgive such unreasonable courage.

-

74. Bodies of abandoned cars in 9 Mile Settlement, Port Moresby. This is the home base of the “Dirty Dons 585” raskol gang that has committed hundreds of rapes during the past decade.

“Now we are very quiet,” says Peter Moses, the former leader of the gang. “I think now my boys rape one woman a week. Before, we used to do it every day.”

-

75. ‘Raskols’ are infamous inhabitants of the settlements of big towns in Papua New Guinea. ‘Once you enter the settlement, anybody can be a ‘raskol’, even me’, joked one of my fixers. Some of the criminals have jobs. They work as bus drivers or security guards during the day and go out at night with their hand-made guns to get extra cash. But a majority of them are boys who left school early and struggle to find jobs in the cities.

“We thought this stealing... the killings, would make our life easier but now we regret that we left school and didn’t finish our studies,” one of the gang leaders said to me. “You regret that you didn’t complete school? What about the rapes and the killings,” I asked, “Do you regret that or not?” “I don’t care to regret about this. This is everyday life. I don’t think about that, I forgot everything, I don’t regret.”

-

76. Richard Bal, who cut off his wife’s ear as punishment for disobedience.

“I got mad with her. I got a knife and just chopped her ear off. She called her relatives. I got 500 kina in cash and paid the compensation. Her parents released this woman back to me, so we stay together again. Recently I broke her arm. She must understand that I am the head of the family. If she can’t come over to this position, I have to do something to solve the problem.”

-

77. A betel nut stain on a road in the Highlands Region.

Buai, the local name for betel nut, is a drug that’s widely consumed in Papua New Guinea. Locals chew it mixed with lime powder and mustard greens. They spit red saliva everywhere, sometimes in front of your feet before even saying hello to you.

Buai stains look exactly like blood. You see them everywhere: on the roads, on the walls of buildings and in the parks. At one point, I saw police beat a woman who was a buai seller. When they hit her face, red saliva came out of her mouth. Or was it blood?

-

78. Michael, 33, an officer from the Kundiawa Police Station, with his weapon in a police car.

Michael: “It’s a new vehicle. It was donated to us by a local politician. We maintain it very well; do not chew betel nut in it.”

Vlad: “What about these red stains on the floor and windows?”

Michael: “Ah, it’s just blood stains. Sometimes we like to brutalize people in the car.”

-

79. Many Papuan men consider women a commodity. When women are young and beautiful, men pay a ‘bride price’ for them, which can include large amounts of money, pigs, seashells, flour and rice. Once a bride price is paid, the woman becomes the property of the men. They may be beaten, tortured or simply thrown out into the street.

Sometimes when women get old they are not needed in their families anymore. In the Highlands, it is not unusual for sons to accuse their mothers or grandmothers of witchcraft so they can kill them without punishment and take possession of their houses and other property. In big towns, there may be no place for old women and they might be simply expelled from the house to sleep in the backyard, where they will not interfere with a young family’s life.

-

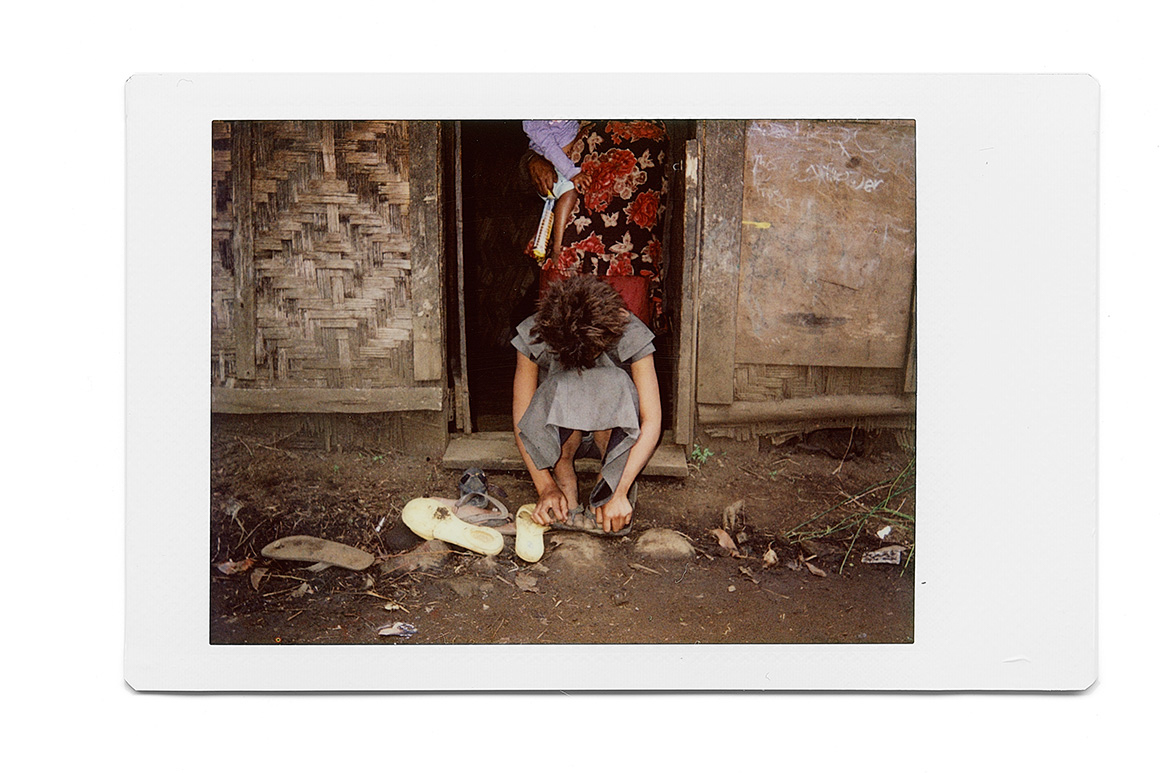

80. Ronni (name changed), 12, sits at the entrance of her family house in a village in Western Highlands Province. When Ronni was ten she was raped by a man from the neighboring village. To escape any legal consequences, the perpetrator offered her parents a pig as compensation. The pig was accepted. Two years after the rape, I visited Ronni’s place with UNICEF representatives. They had arranged in advance to interview Ronni’s mother but, when we arrived, the mother refused to talk. She said she had changed her mind about the interview and decided not to rake over old pains.

“We were paid for Ronni. Now we are friends with the family of the man who hurt my daughter. If they find out that you have asked us about that they may claim the compensation back.”

-

81. Annie (name changed), 15, in a Mount Hagen brothel. Annie lived with her sister and her sister’s husband. Her brother-in-law forced her to work here so that she could pay for food and accommodation while staying in his house. Annie said that she has four to five clients a day.

The owner of the brothel gave me permission to speak with Annie. However, while I was talking to the girl and taking pictures, he burst into the room. I could smell alcohol on his breath. “You have entered the girl’s room, so you must pay!” he said, infuriated, hitting at me with his fists. Drunken brothel clients headed toward us. My guard pushed the brothel owner to the wall and shouted at me to run to the car. I ran down the stairs and jumped into our ‘armored vehicle’, a car with the bars across the windshield, and we left. Later, I called Annie to ask if she was ok. “Everything is alright,” she said, laughing. “Sorry for that guy, he was just drunk. Could you call me later? I can’t talk right now. I’m with a client and have to work.”

-

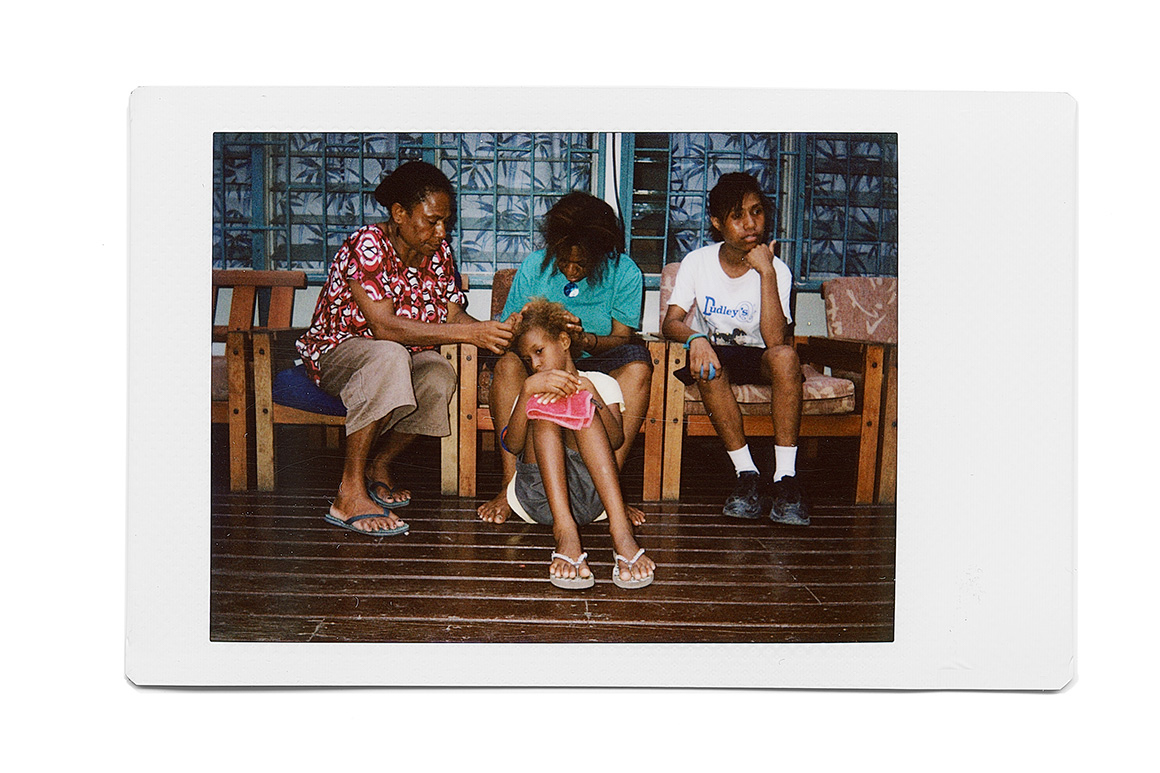

82. People in Haus Ruth refuge. I kept coming to Haus Ruth again and again, almost on every visit to Papua New Guinea. This refuge center is located near the famous Ela Beach, where families usually go for weekends. From the barbed wire fence, through the iron bars on the windows, women and children survivors can watch how people barbeque, how kids play in the water... But behind the well-guarded walls of the refuge, victims and survivors still live in fear despite being considered the ‘lucky ones’ - those who managed to escape the violence and receive a temporally shelter.

They tell me horrible stories of their lives, stories that you would never imagine in your worst nightmare. They share all their pain with a complete stranger with a camera, hoping that somehow I can help them. Every time I leave Haus Ruth, I am devastated. I know that not all the stories that they shared with me will be published. Some editors will find them too shocking and the photos too graphic.

-

83. Jacklyn with her children came to Haus Ruth refuge center in Port Moresby after escaping her violent stepfather. “When I was five my mum remarried. My step dad was an alcoholic. He would come home and beat my mum and tell her ’Take this bastard out of my house!’ And I would be there watching. And I didn’t know who the ‘bastard’ was. And I would wonder what this word really meant. But with all the treatment I was getting I realized that... I was the bastard in the house. My mum... ran away. I was left to stay with my step dad... Physically he used to really kill me half dead. He broke my nose... I have several scars on my head. He broke my finger, my lips... I used to carry a black eye and go to school... He paid a bride price for my mother...

-

84. Working on the same project for years, following the same people, gives me an opportunity to see changes in the lives of the women I photograph. I met Helen Michael early in 2012, a few weeks after she was attacked by a ‘cannibal’, a crazy man who bit off her lip. Police arrested the man but, because Helen spent several days in the hospital and submitted her complaint ‘too late,’ the man was released. She didn’t give up fighting for justice and went to the media. That’s how I first heard about her. I called the local paper, police, and hospital looking for Helen. Everyone had heard this terrible story but no one could help me find her. One day, I was passing a square in the center of Port Moresby and saw a woman walking in my direction. On her lower lip I saw a bandage. When she came closer to me I looked at her face and noticed under the bandage, instead of her lip, there was a hole with teeth. I stopped her and carefully asked if she might be that woman from newspaper story. It was her. I could not believe my luck to find Helen by chance. I took her portrait and showed it to some organizations. ChildFund and Interplast offered their support to her. Two years after the attack, Helen went through plastic surgery. Her lip is back now and her scars are healing. Her story inspired many women from her settlement. Now she is advocating in her community to stop the violence.

-

85. Having documented violence against women in Papua New Guinea for three years, I kept looking for a family without domestic violence. In a small Papuan village called Hanuabada, I met with Dogodo Naime and his wife Gabe Igo, who had been married for more than 16 years. They had not quarreled during their marriage. When I met them, Gabe was seriously ill and had only a few months to live. During the previous four years, Dogodo had taken daily care of her, fed her, helped her to wash and change her clothes. After her death he became weak and almost never left the village.

“My friends tell me to find another wife and start enjoying life again. I tell them that until the ground on Gabe’s grave subsides I will not look at any other woman.” In a country where polygamy is standard in some areas and rates of violence against women are among the highest in the world, it is rare to hear statements like this from a man.

-

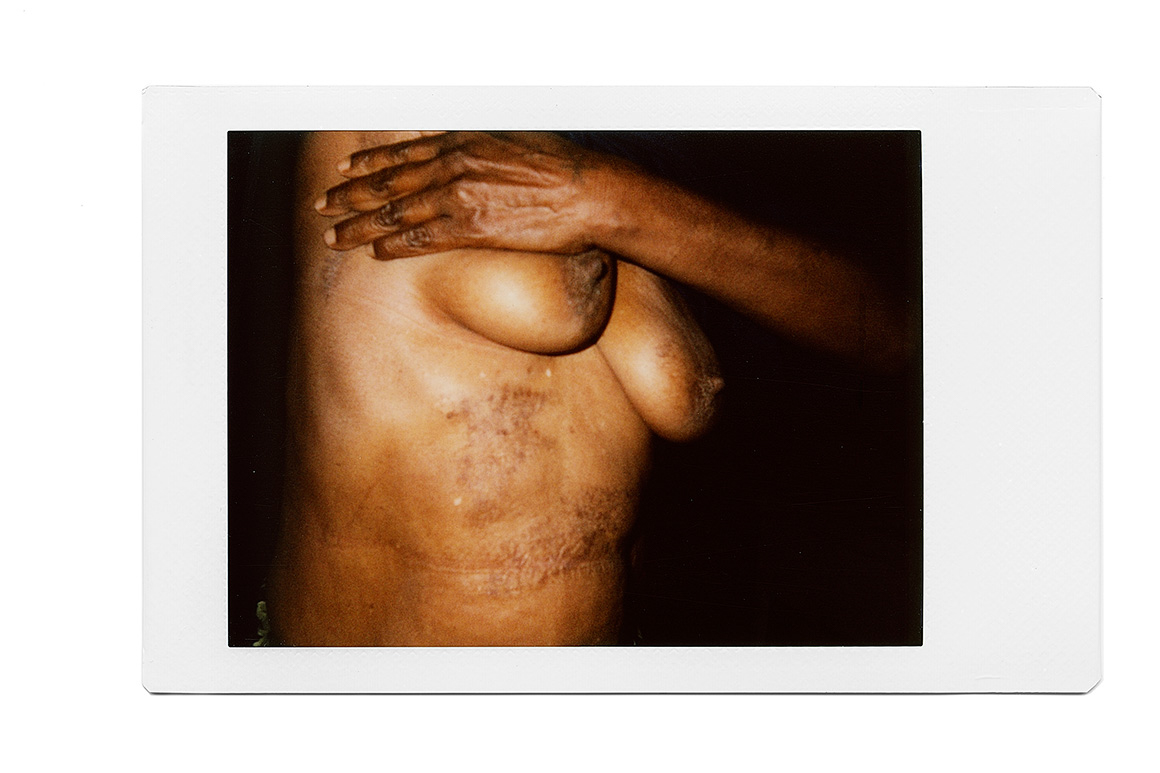

86. Dini Korul, a sorcery attack survivor, shows the wounds inflicted after she was accused of using sorcery to kill her son.

“They came to my house,” Dini said, “they dragged me to the road. There was an old house. They took me inside and they closed the door. They took off all my clothes. They made a fire and cooked the knife. They put it on my skin, took it off and put it back again. They pushed the knife through my side and it broke my bladder. They locked the door and they left. I was in the hospital for almost one year.” Dini was saved by women from another village who were passing by and heard her groans.

-

87. A year before this photograph was taken, there was a pigsty here. This is where Dini Korul was tortured. Later, the shabby building fell apart, but Dini’s children still remember how their mother, nearly dead, was rescued from there after the brutal torture.

The villagers, who never apologized to Dini, also remember that attack. It is my fourth visit to the place. The local men who took part in the torture look at me and my camera with mistrust. Not long ago, I learned that Monica Paulus, a local human rights activist who works with me, had told everybody that I was a doctor. She said I had visited Dini with drugs, taking her photos only for medical reports. “This way it would be safer for everyone,” Monica said.

-

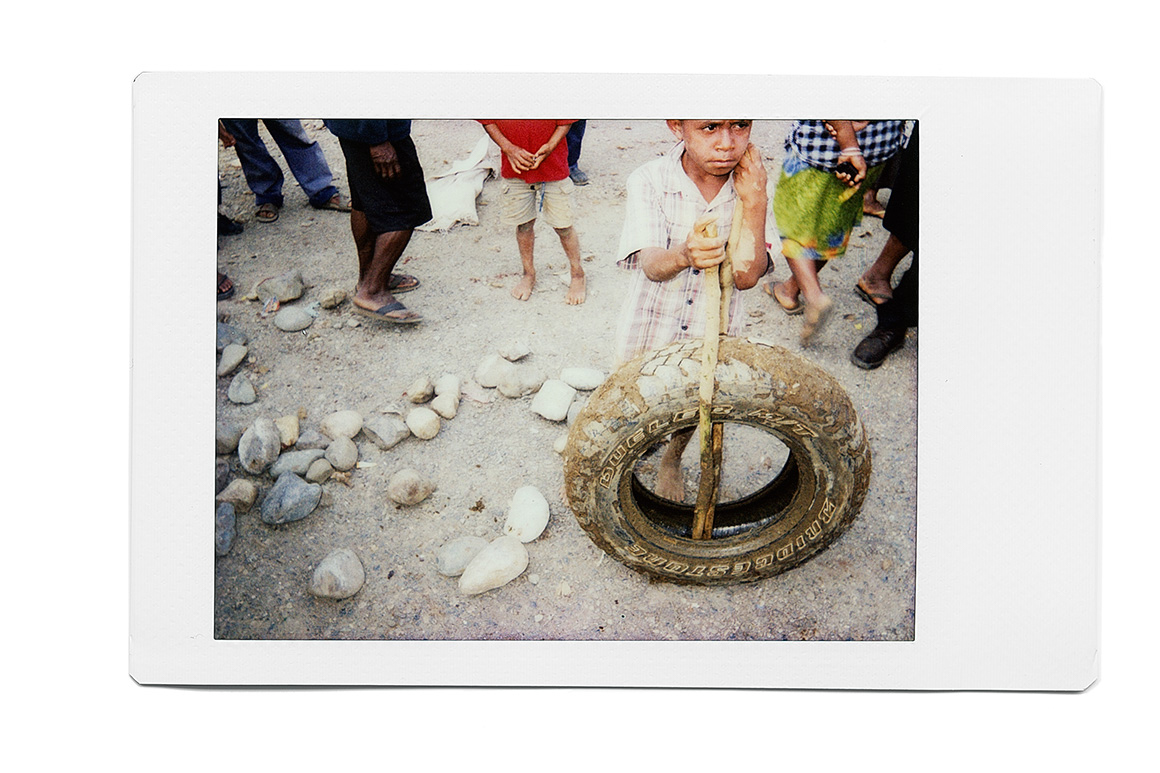

88. A boy plays with a tire in the city of Mount Hagen. He is playing where a 20-year-old woman, Kepari Leniata, was burned alive on February 6, 2013. Kepari was tortured after being accused of using black magic to kill a young boy from her settlement.

I visited this spot two weeks after Kepari’s death. A couple of local women were selling betel nut there. Within five minutes the place became crowded. Lots of people came to see what the white man wanted. I asked kids if they had seen the torture. This boy told me that he was near when people “cooked sanguma meri” (sanguma is Pidgin for witch). I wanted to ask him more questions, but people started shouting at me. They pushed me back to the vehicle, asking me to leave, saying that it was not a white man’s business.

-

89. I cannot stop wondering why some perpetrators tell me how they raped, tortured or killed women accused of sorcery. They tell me terrible stories willingly and include graphic details.

Ilai Nul, from Chimbu Province, is one such man. In 1982, he killed an elderly woman accused of sorcery. Before the murder, he cut off all her fingers and thumbs, one by one, forcing her to admit that she had been involved in witchcraft. When asked how he felt about what he had done, he said he was sorry. “That woman was like a mother to me,” he said.

-

90. Wendi, from Chimbu Province. In 2011, Wendi’s neighbors accused her of sorcery. They locked her in her house for three days with no food and came every night to torture her. They burned her body with hot metal, forcing her to admit that she was a witch, and demanding that she name other witches. Wendi was saved by a human rights defender, Monica Paulus. Monica heard about this incident and called the police. It is one of the few cases I’ve heard of when the police came to save someone without asking them to pay for fuel.

Having survived the torture, Wendi went into her shell and almost stopped talking. The villagers think that she became crazy. I think she has not recovered from the trauma of what happened to her.

-

91. Maria’s grave.

Maria was a woman from Chimbu Province who was accused of sorcery by her grandson. On the night before the attack, he was drinking and smoking drugs with his friends and they were talking about sorcerers. Someone said that his grandmother was probably a witch. In the morning the boy went to his grandmother’s house. She was cooking him breakfast to take to school. He chopped her head off with a bush knife.

Another victim of a witch-hunt, Dini Korul, took me to Maria’s grave and told me this story. Dini’s son Bobby was buried nearby.

-

92. Emate with her youngest son Dikon. She survived a brutal attack but had to pay for her medical treatment.

I met Emate at the hospital three days after the attack. She had bandages all over her body and was barely able to speak. She said that she was tortured by four men, her relatives. Only a year later, Emate told me that three of those men were her sons. They never apologized to her. After leaving the hospital, she grabbed her youngest boy and left her village for good. She never saw her older sons again.

I wonder what it is like to live in such pain, knowing that your own flesh and blood wanted you dead. Human cruelty truly knows no bounds.

-

93. A new prosthetic hand of Mama Rasta that she got from an American doctor after 10 years of suffering. I met Rasta in April 2012 and, since then, I visited her on almost every trip to PNG. We became close friends. Her story is shocking and I applaud this woman for her will to live despite the trauma she experienced. Rasta: “I was around when one man died, and they (villagers) said: “you are ‘sanguma’ and you killed this man”... So they cut off my hand. When I wanted to block the bush knife with my other hand, they cut off my finger. But I don’t do ‘sanguma’, they just cut me for no reason... I survived and stayed for four days at Kujip hospital and then doctor Jim from America released me to go home. With just one hand I can work, I can chop my own firewood. I fetch water by myself and carry it inside the house. I can plant and dig up my sweet potatoes in the garden. But sometimes it’s hard for me to peel sweet potatoes, so often I give up, I just cook them as they are”.

During one of my visits to Mama Rasta’s village, I went to Kujip hospital, to interview doctor Jim, the same doctor that helped Rasta ten years ago. He told me that by coincidence another doctor from the US was about to come to the province and bring a few dozens prosthetic arms to give for free to disabled people. Doctor Jim put Rasta on his patient’s list and she was the first to get a new prosthesis a week later.

-

94. Julie’s prosthetic leg. Julie’s father chopped off her leg when she was nine months old.

“I don’t remember it myself, but people say that my father had a fight with my mother and he chopped off my leg during the fight,” said Julie. “Mum brought me to the hospital and never came back. When I was 17, I went to Lae hospital to make a new false leg. Raskols attacked me on the street and raped me. I got pregnant then. I love my son. He is everything I have.”

-

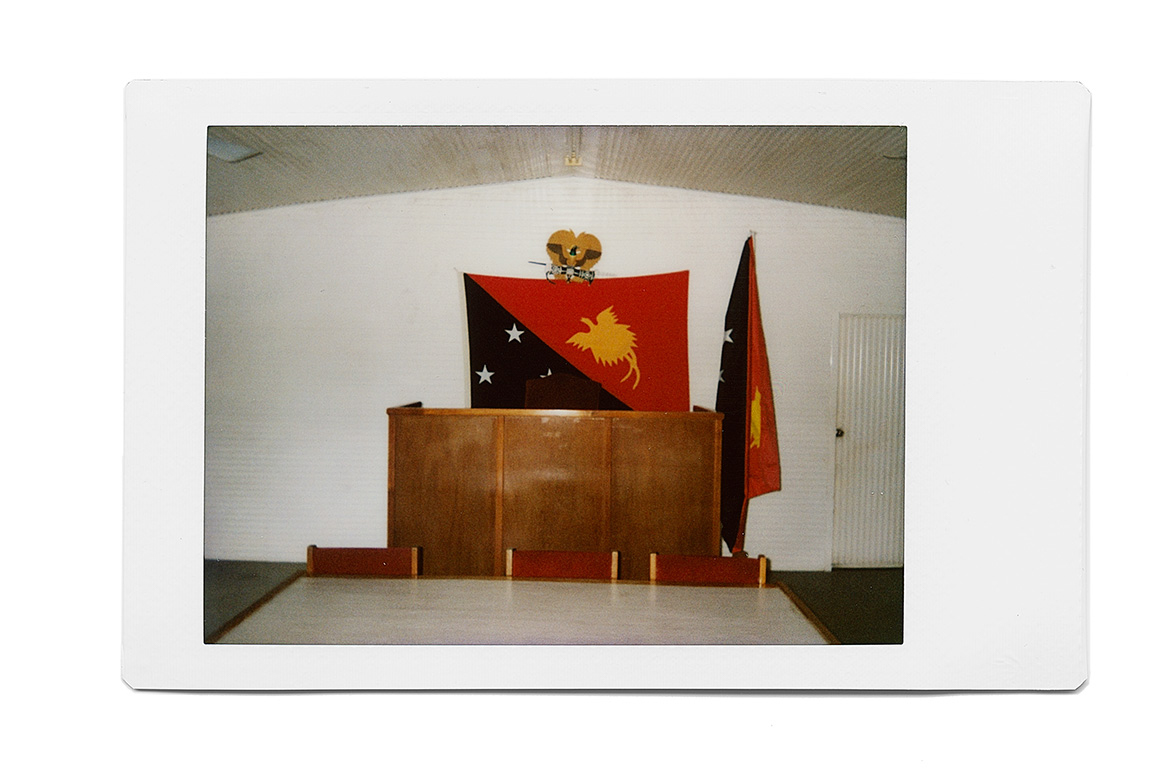

95. The office of the District Court in the village of Kwikila, Central Province. Each day courts in Papua New Guinea hear many cases of rape, torture and domestic violence that affect women and children. But the reported cases are only a small percentage of the crimes committed.

In order for police to visit a crime scene, they generally request that victims pay money to cover their fuel costs. If that money isn’t paid, police cars rarely reach the crime site. Even after being arrested many perpetrators avoid justice. Criminals who have gone unpunished proudly tell, like jokes, their stories about how they have avoided ending up behind bars. Some provincial judges still apply laws that were repealed long ago. Letters notifying judges of changes to the criminal code are sometimes lost and never delivered.

-

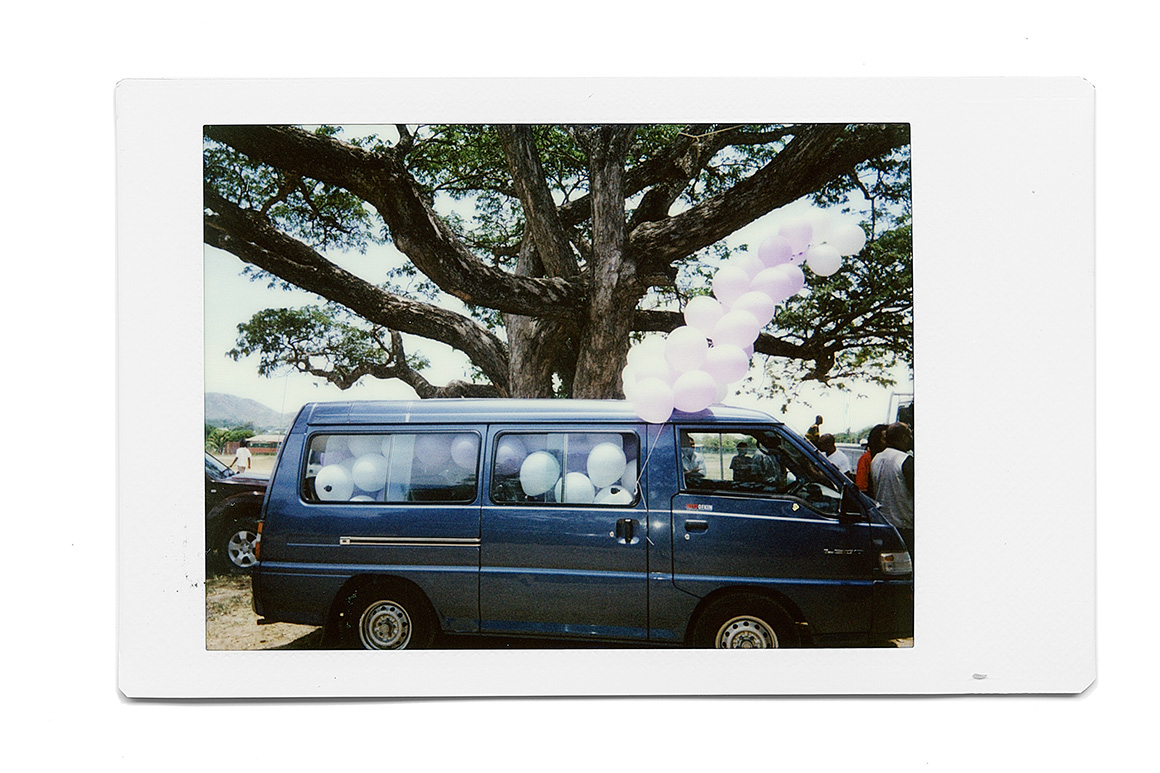

96. Balloons symbolizing the victims of violence. The balloons were prepared for an international protest against gender violence in Port Moresby. Jack Padik Park, in the city’s 5 Mile area, was crowded with people. Human rights activists, church leaders and politicians made speeches from the stage. Again and again they said that violence was not acceptable.

Best of all the speakers was a woman who came to the stage to share her experience, “I said to my husband, I don’t want to have children with you,” she said, “When I was a little girl, I was raped by raskols. After the wedding you started beating and raping me. I don’t want to have a daughter to be born and brought up in the society with such traditions. There is no future for women here.”

-

Crying Meri: Violence Against Women in Papua New Guinea is a long-term documentary project by Vlad Sokhin. Vlad started documenting gender-based and sorcery-related violence in PNG in January 2012. In the following three years he worked on his own and in collaboration with several print/online media companies, the United Nations and international NGOs.

-

In addition to the main photo project, Vlad worked on several multimedia features and short documentaries that bring additional focus to the horrific culture of violence towards women and girls in PNG:

– Open Eye Crying Meri, a radio documentary, produced by duckrabbit for the BBC World Service, and presented by Vlad.

– Crying Meri. A multimedia film that tells the story of Dini Korul from Chimbu Province, a woman who was accused of sorcery and brutally tortured. It’s a harrowing, unflinching account, but it’s a story that needs to be told inside and outside a country where women are literally dying to be heard. The film was produced by duckrabbit and Vlad and published online by The Guardian.

– Sorcery Related Violence in Papua New Guinea (10:21 min). A documentary film produced by Vlad for UN Women in 2013 (to be released soon).

– Helen’s story and Helen’s recovery. Two short multimedia pieces that tell the story of Helen Michael, a woman from Vlad’s Crying Meri photo project. Helen was attacked by a stranger who bit her lip off. Two years later ChildFund Australia supported Helen throughout the process of hospitalisation. Doctors from Interplast Australia & New Zealand performed plastic surgery and fixed Helen’s lip. Vlad produced videos for ChildFund Australia, which were used in ChildFund’s campaign against gender based violence in PNG.

-

– Domestic Violence in Papua New Guinea. Another short multimedia film Vlad produced for ChildFund Australia’s campaign against gender based violence in PNG. This video shares Taina’s story, a male community leader in PNG who regrets having once been a violent man. It also features Helen and Kay, two women who hope that people will hear their stories and take action.

– Images from Crying Meri were adopted by the United Nations for educational campaigns and used by Amnesty International, Oxfam, ChildFund, World Vision, The Resolution Project, OilSearch Health Foundation and other organisations that support victims of gender-based violence in PNG. They appeared in online campaigns, protest marches, PNG National Haus Krai, and in United Nations and NGOs reports and magazines.

– In 2014 Crying Meri was published as a hard copy and iPad e-book by FotoEvidence. It includes Vlad’s polaroid diaries and his work notes.

– The project was exhibited and screened around the world, including the Parliament House of Papua New Guinea; Australian Parliament House in Canberra; Visa Pour L’Image photojournalism festival (France); Head On photo-festival (Australia); the United Nations exhibition in University of Papua New Guinea; VII Agency Gallery (USA); PNG Human Rights Film Festival; Chiang Mai Documentary Arts Festival and others.